Meet some of the members who work with agroecology in Europe

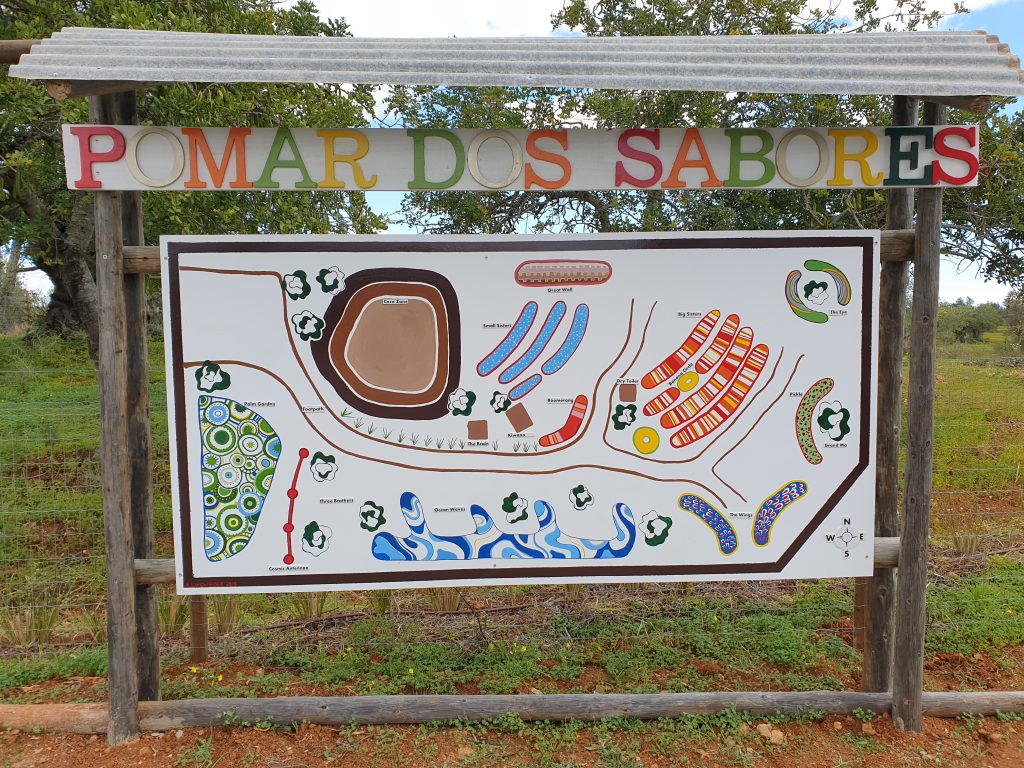

Miguel Cotton's Orchard of Flavour (pomar dos sabores)

Tavira, Portugal

A botanical garden dedicated to fruit trees of warm climate

Miguel Cotton created Orchard of Flavours, a botanical garden dedicated to fruit trees of warm climate located in Tavira (Portugal).

The most important goals of this botanical garden are to show which fruit production can be relocated to Europe and to share all the knowledge necessary for the success of their own efforts. Emphasis is placed on the establishment of several varieties of the same species in order to discover different flavors and different maturation periods, as well as to determine the species most suited to the climate or the soil.

“Incredibly impressive garden project with a variety of exotic fruit trees and aiming to find varieties that could be used in the region, taking into account issues such as water scarcity, ecosystem diversity, etc.

Miguel’s enthusiasm for trees and plants is contagious and a tour with him through the project is a real experience and very educational!”

Florian ( Pays-Bas, September 2021)

Read more about the project here!

Pietro Ganni: Chef at the museum of Biella's territory; President of Ethnobotany and Gastronomic diversity association (Egda)

BIELLA IN Piedmont, ITALY

The influence of the Anthropocene on the circulation of traditional dishes from the Piedmont region and first ''tastes'' of typical agroecological cuisine.

Definition of the agroecological cuisine concept in the foot of the mountains and mountains

The continuous process of human evolution, the pursuit of his needs, and the increase of his activities on earth lead to either the deterioration or improvement of gastronomic traditions.

Agroecological cooking consists of adopting innovative ecological principles in the preparation of dishes representative of a specific place. Where possible, the collection of indigenous, free-growing plants, including fruit, that grow in natural ecosystems is favoured. Meat and fish should come from locally sourced agricultural and zootechnical agrosystems, of low-yield production. Vegetables are grown by small producers in the area.

This philosophy is applied to restaurants through the organisation of multisensory gastronomic events such as lunches, dinners, snacks and refreshments, using the most innovative approach possible. For example, in redesigning traditional recipes or preparation methods, or novel design to the dining room interior, crockery used in laying the table, or novel forms of waiting for service.

All activities in the territorial dining facilities are mediated by gastronomic facilitators: young cooks, even those with discrete practical experience, who are enthusiasts of the ecology and gastronomy typical of the place where they were born and raised. The latter, collaborating with active local chefs and cooks, dining room maître, agroecologists, experienced farmers, even gastronomic curators, will aim to form a territorial gastronomic research and training group.

Over time, the continuous exchange between local workers will encourage the organisation of various gastronomic events in the facilities in which the activity will be held.

‘Redesigning the past to plan a for a better future” – Achille B. Oliva

Membership

The facilitator chef should only serve typical gastronomic specialities that are representative of the hosting restaurant (or that represent the chef’s cultural and ethnic characteristics). The preliminary arrangement between the gastronomic facilitator, the chef with his team, and the research group will allow establishing if and how to make improvements to some dishes or whether to interpret new ones, always respecting the originality of the typical products and their history. This experimental approach to traditional cooking can be applied more efficiently to small farms, biocultural mountain huts, taverns, and small restaurants.

Aims of the Piedmont agroecological kitchen project

- Promote the knowledge of authentic traditional Biellese and Piedmontese cuisine through the study and reworking of typical dishes.

- Encourage the collaboration between gastronomic operators in the area to promote food and the right to ‘simple pleasures.

- Opening the mind to young people who intend to deeply understand the details of the language of food and wine tasting.

- Encourage self-sufficiency, resilience, and food sovereignty of small businesses in the Italian foothills.

- Contribute to the re-evaluation and discovery of the floristic and gastronomic biodiversity of the foothills of northern Italy.

- Provide alternative methods of preparation for traditional Alpine recipes where necessary, and new techniques in utilizing ingredients (fermentations, extractions, foams).

- Critically interpreting the local tradition without being overly nostalgic.

- Coin new ‘traditional’ dishes with traditional or typical ingredients.

Whether the above principles are followed, diners will be able to enjoy a new multisensory gastronomic experience, which will amplify the knowledge and recognition of a new and stimulating typical cuisine with simplicity and elegance.

Luuk’s farm: a hotspot of culture and biodiversity

Maartensdijk, The Netherlands

Many farmers’ sons and daughters in the Netherlands no longer want to take over the farms of their parents. They see that farming is a life of hard work, lots of financial worries and little appreciation from society. They also see that the countryside is emptying and that choosing for farming is to choose for a life of isolation. Or so it seems. In the last decade a movement of new farmers has emerged in the Netherlands. They circumvent retailers, banks and other actors that in the food chain that put financial pressure on farmers. And create new, local markets that allow them to produce in an agroecological way. They also turn isolated areas into hotspots of culture and biodiversity.

Luuk Schouten is one of these farmers. He graduated as biologist at the Wageningen University and became an environmental advisor. In 2007 he started the vegetable farm Eyckenstein as he “wanted to do something real”. On 0.7 hectare Luuk cultivates a large variety of vegetable including carrots, beans, zucchini, pumpkins, lettuce and parsnip. One can buy the vegetables at the farm or by subscribing to a vegetable box. Luuk: “For me it is important that sustainably produced food is affordable. I can realise this through direct sales.”

People come not only for the vegetables but also to enjoy the peace and beauty of the place. They come to enjoy the various flowers that colour the farm and admire a restored greenhouse that was built in 1900. Luuk: “Next to cultivating organic vegetables we want the farm to be a place where visitors, volunteers and people passing by feel welcome.” The farm is also a place of work and learning. Luuk works with about fifteen volunteers. Some of them do this as part of an internship for their studies, others are form the neighbourhood. They help with applying manure, planting, weeding, harvesting but also with making decisions on the farm. With two interns Luuk has for instance made changes to the cultivation plan.

The case of Luuk illustrates how new farmers are revitalising rural areas in the Netherlands. Creating places that produce not only diverse, healthy and sustainable food but that also produce biodiversity, social cohesion, beautiful landscapes and education.

Contact: Luuk Schouten, contact@landgoedgroenten.nl.

Website: landgoedgroenten.nl

This text is based on: Leonardo van den Berg and Maria Alice Mendonça (2018). Bruisend leven op de tuinderij. Nieuwe Markten: Delen in de voedselketen, a publication by Toekomstboeren, the association of Dutch peasant farmers and a members of La Via Campesina.

LIVESTOCK IN A CIRCULAR ECONOMY: SAINT MICHEL FARM

WASMES-AUDEMEZ-BRIFFOEIL, BELGIUM

Anne-Marie and Jacques Faux-Vandeputte: “St Michel farm was built on the grounds of a former inn by the end of the 18th century. Since 1745, the place has been owned by our family. We have been living here since 1980. At that time, the farm was mainly oriented towards traditional crops (cereals, sugar beets, potatoes). In the nineties we decided to switch to keeping livestock (limousine cattle and farm poultry – chickens, turkeys, ducks) while striving for a good balance between meadows, cultures and animals.

We have constantly been seeking a maximum of fodder autonomy. This brought the farm into a certain circular economy: the animals transform a part of the crops and their by-products into manure and, in turn, the crops recycle animal manure which keeps the soil healthy and biodiverse.

On the basis of this philosophy, we recently switched to organic farming. All livestock production is directly sold to local consumers, either by a local co-operative, or through the farm shop. The latter nurtures our close relationships with the customers and helps us to understand their wishes. One example is that we are currently engaging with a consumer group to develop alternatives to plastic bags and packaging.

We are also involved in various other social activities. We transformed an ancient stable into a guesthouse where we welcome guests from abroad,and a handicapped person works on the farm every week. We occasionally shelter a refugee on the farm, who also participates in the work. If you would ever like to visit us, you are very welcome!”

Contact: Ferme Saint-Michel, Anne-Marie and Jacques Faux-Vandeputte, www.fermesaintmichel.be/welcome

GROWING OLIVES IN CENTRAL GREECE WITH AGROECOLOGICAL PRINCIPLES

THESSALY, GREECE

Vassilis Gkisakis: “I am an agronomist and farmer at a small scale olive farm, located in a hilly zone of central Greece (Thessaly). My family has owned the farm for 4 generations. My very first steps were, literally, among the olive trees, which has undoubtedly contributed to my decision to become an agronomist.

The farm consists of an olive orchard, approximately 6 ha, accompanied by another 14 ha of cereals and fallow land. The farm is organically certified and it can be considered of High Nature Value, as it is located within a broader protected Natura 2000 area. We farm using agroecological principles, including high use of associated biodiversity, preserving large strips of hedgerows of native trees and bushes, targeted mass trapping of olive pests such as the olive fly and establishment of on-farm semi-natural habitats for beneficial insects (parasites and predators of olive pests). Irrigation water is saved from a neighbouring brook as well as through rainwater harvesting, making use of warehouse roof-tops connected to tanks.

To improve our soils, we practice no-tillage. Instead, we cut the weeds which provides a valuable mulching layer, helping to save irrigation water and considerably increasing soil fertility. We fertilise by using legumes like vetch, as well as manure provided by a nearby sheep livestock facility, owned by a related family, and other minimal inputs, such ash residues and trace minerals (Boron). As a result, our soil analyses of the last years demonstrated a steady organic matter level increase in the orchard.

The productivity of our table olives is remarkably high, despite the low input approach; peak harvests of approximately 2,5 tons of olive/ha has been reached, although alternate bearing is a frequent phenomenon in olive production. We store and process the olives in large tanks, treating them with water and salt in order for them to become edible.

We usually sell the olives as well as olive oil in open farmer markets and local grocery stores. This provides us with an income that is at least three or four times better than if we would sell to a middleman. Indeed, the income of family farms in Greece is generally low, which means that today, farming often provides only complementary income.

The main challenge for Greek olive producers and the rural sector as a whole will be to fully exploit the potential that high levels of local agricultural knowledge and a biodiversity-based agriculture can offer, together with socio-economic arrangements such as short, local and independent market chains and cooperatives. The agroecological approach, although relatively new to the Greek rural sector, allows for the combination of traditional farmer practices with recent innovations, and so help meet sustainability and environmental goals of the future.

At our farm, we faced hard challenge three years ago when a huge fire broke out, severely damaging the orchard. It appears to have recovered quite well, which we think can be attributed to the resilience of our farm which has increased through our agroecological approach.”

Contact: Vassilis Gkisakis, https://www.linkedin.com/in/vgkisakis/